Hurting Children to Protect Them

“Those in authority must retain the public’s trust. The way to do that is to distort nothing, to put the best face on nothing, to try to manipulate no one.” -John Barry, The Great Influenza.

I am currently serving in a COVID advisory group for the school district where I live in Indiana. The purpose of the group is to advise the superintendent and the school board how to deal with COVID cases, when to implement or relax quarantines and mitigation strategies, and how to avoid the disastrous shutdowns the school district was forced to endure in 2020. It is a worthy goal, and I’m happy to be a part of that effort.

It is clear that school closures prevented children, particularly from low-income families, from receiving educational opportunities and health-promoting programs. Many young children didn’t even start school. In some places children were set back 4-5 months due to school closures and subpar remote learning. Child abuse, obesity, and suicide attempts increased as mental health declined. Drug overdoses soared. My wife, a public health researcher, talked with a social worker at the local Division of Child Services, who relayed that she was receiving five calls a day compared to five calls a week prior to the pandemic. Another DCS worker told me that she and her co-workers were responsible for helping disadvantaged kids with remote learning. Not surprisingly, it was a thankless, and nearly impossible task, and many children suffered as a result.

In hindsight, school closures and remote learning were a disaster. It’s therefore worthwhile to ask the question: Do the benefits offered by our current in-person school mitigation strategies clearly outweigh the harms?

Exaggerated Harms About Child Susceptibility and Spread

Unfortunately, it isn’t just masks that have been irredeemably politicized during the pandemic. Public messaging about the susceptibility of children to severe disease and their role in transmission of SARS-CoV-2 were distorted for political purposes and financial gain from the beginning.

For me, this was completely unexpected. I had interactions with friends on social media early on, and I had thought that I could reassure them that evidence suggested their children would be OK. Not only did they not believe me, it seemed they didn’t want to believe me. They had been watching 24-hour cable news, reading The New York Times, and listening to NPR. What I was saying sounded absolutely nothing like what they were seeing, hearing, and reading. I had run into a wall of cognitive dissonance impossible to overcome.

This was incredibly frustrating, because early evidence did suggest that children were not susceptible to severe disease nor were they super-spreaders. The average age of COVID-19 mortality in the northern Italy outbreak was 81, and reports from Chinasuggested children were much less likely to get severe disease. The fascinating DECODE study in Iceland used viral sequencing to determine SARS-CoV-2 transmission patterns, even within families. An investigator in the study said in an interview that “children under 10 are less likely to get infected than adults and if they get infected, they are less likely to get seriously ill. What is interesting is that even if children do get infected, they are less likely to transmit the disease to others than adults. We have not found a single instance of a child infecting parents.”

Despite the early evidence, media stories and speculation about child spread of SARS-CoV-2 were rampant. On July 18, 2020, the New York Times covered a study from South Korea that claimed children spread SARS-CoV-2 as easily as adults.

This was published at a time when schools were deciding how to return to school in the fall of 2020. As a result of this and many other stories, thousands of schools throughout the U.S. decided to go completely to remote learning in the fall.

One month later, the same reporter wrote a follow-up story acknowledging the faults of the South Korea study:

“A study by researchers in South Korea last month suggested that children between the ages of 10 and 19 spread the coronavirus more frequently than adults — a widely reported finding that influenced the debate about the risks of reopening schools…But additional data from the research team now calls that conclusion into question; it’s not clear who was infecting whom. The incident underscores the need to consider the preponderance of evidence (emphasis mine), rather than any single study, when making decisions about children’s health or education, scientists said.”

But the follow-up article wasn’t as widely circulated as the first, and the damage was already done.

Misinformation about the role of schools and children in SARS-CoV-2 spread continued, perhaps most perplexingly, along with a complete lack of curiosity as to what was happening in schools in the rest of the world. For example, primary schools remained open in 2020 Sweden, with no masks, no deaths, and no adverse consequences for 1.8 million children. Teachers had an average risk of infection compared to other occupations.

Misleading information and fear about risks to children continues to be widely circulated, especially in the U.S. The most obvious explanation is that this is part of a campaign strategy to increase the acceptance of vaccination for children. But this requires a serious distortion of the truth, a willingness to ignore the needs of developing countries, and has resulted in a loss of trust in public health.

Masking in Schools is as Politicized as Universal Masking

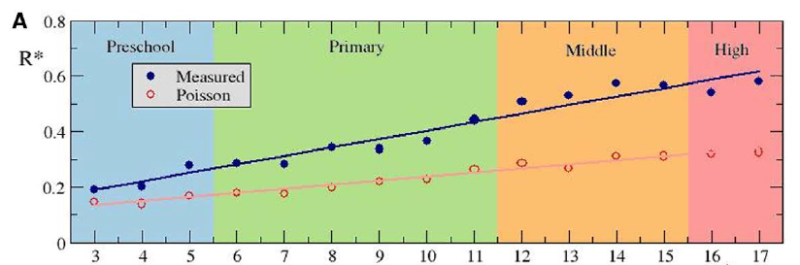

Sweden isn’t alone in relaxed school mitigation policies. Many other countries do not require masks in schools, including Norway, Denmark, Switzerland, Netherlands, United Kingdom and Ireland (for ages 5-11). In spite of mask-optional policies in the U.K. in fall, 2020, attack rates in school outbreaks were low for students, especially in primary schools. Instead, teachers were primarily the source of spread, although their positivity rates were no higher than other workers. In the U.K., U.S., Italy, Spain, and Australia, school case rates were commensurate with community rates, indicating that schools are not major drivers of community outbreaks. In Spain, the average number of individuals infected by an index case didn’t rise above 0.6, and was the lowest among unmasked preschool-age children (<6 years/age):

Despite all of the interest for masking children in the United States, there are few studies with results that clearly support mask requirements for students in schools, and requirements may significantly disrupt learning. One well-publicized study in Science relied on results of a Facebook survey, did not consider testing levels in different areas and only found significant differences with teacher masking (shown by added red arrow, right) when COVID-like illnesses (CLIs) were counted (green), while no differences were found with student masking (added red arrow, left) when positive NAAT results were required (purple).

Another study with an outsized media footprint is the “Duke Study”. The authors claimed that masking in North Carolina was effective in reducing cases in schools. They were given a large platform for their claims with an article in the New York Times. The only problem—all the schools analyzed had mask requirements. “We don’t have data from within North Carolina as to whether or not, in school in K-12, what happens when children are not masked.”

Despite this oversight, the authors did make some interesting points about the effect of quarantines and risks of COVID in children: “More than 40,000 people (staff and students) is hundreds of thousands of school days that have been missed because of quarantine. And yet the benefit that we’re seeing is nil…the risk of death from acquiring COVID and dying from it in North Carolina (for students) this past year was less than the risk of riding to school in your parent’s automobile.”

If the risks to children are that low (and they are), then why are masks necessary? Why waste time arguing over the evidence? However, as long as the CDC continues to recommend masks for children 2 years of age and older, the debate will continue.

In contrast to the Duke study, the National COVID School Response Dashboard data concluded that mask requirements in Florida had no relationship to the number of school cases. However, like other researchers that have reported negative data since masking became increasingly mandated, the dashboard’s creator Dr. Emily Oster has indicated that she is still in favor of school masking. Dr. Oster’s group has launched a new COVID-19 School Data Hub that will expand data collection and hopefully publish updated results. It will unfortunately be in her best interest that the new data support school masking and other school mitigation policies in order for her not to be portrayed as a villain. As I demonstrated in the previous article about universal masking, expressing contrary opinions and reporting data that does not support masking frequently results in public reversals, softening of positions, or re-evaluating unpublished data to fit the current political environment.

As with universal masking mandates, it should not be surprising that the conclusions of CDC-sponsored studies support their school-masking recommendations. A study examining the effects of masking and ventilation in schools in Georgia found a significant reduction in cases when masks were required and ventilation was improved in classrooms, but only among teachers and staff. Furthermore, the study design could not distinguish which improvement had the most effect, and did not consider community cases or testing rates.

In two more recent CDC studies, researchers compared the association of mask mandates with cases or changes in case rates in the two most populous counties in Arizona or using county-level data across the U.S. In the Arizona study, the authors report a whopping 3.5-fold increase in the odds of a school outbreak in schools without a mask requirement compared to mask-required schools. This is remarkable because it is an outlier among mask studies; even those with conclusions that support masking have much more modest effects. In the broader U.S. study, analysis of county-level data showed counties where schools had no mask requirements had larger increases in COVID cases during the two-month study period ending on September 4, 2021. Both studies didn’t control for vaccination rates, and in the U.S. study the non-requirement group had a higher baseline case rate prior to the study period; this could be indicative of geographical differences, as there were surges in cases and likely more non-mask-requirement counties in the southern states during the summer months. It is unknown if mask requirements will maintain the reported effects beyond the reported study periods in both studies. Further criticism of both studies can be found here.

Several weeks ago, a new collaborator was explaining why he chooses other labs (like mine) when seeking out new infectious disease models to test his treatment. He told me that his lab could do these experiments themselves, but it was much more compelling to bring in a group from the outside to show the effects can be observed by anyone. In other words, it is critical that supporting data be provided or replicated by disinterested partners. That is how science advances—in spite of individual, group, or organizational biases.

This hasn’t happened for masks, as the conclusions of CDC studies have been vastly more supportive of universal and school masking than non-CDC studies. The CDC should have an interest in showing that its recommendations are evidence-based and free from political influence, contrary to recent history and the political nature of the organization. From an honest and impartial media, their results should invite more scrutiny, but there’s no sign of that happening any time soon.

Quarantines are the New School Closures

As in many states, schools in Indiana are dealing with how to keep schools open despite high-levels of testing that have resulted in excessive students and staff quarantined during surges (as Indiana has had for the past two months). Unfortunately, Governor Eric Holcomb has directly linked quarantines with masking, and unmasked classrooms have much stricter quarantine rules. This is in effect a mask mandate and will further cloud the ability to determine the effects of these interventions on school transmission.

Like school mask requirements, it is also unclear if quarantines of close contacts has a clear benefit in prevention of transmission, despite obvious costs. A recent study in the U.K. concluded that replacement of quarantines of close contacts with daily testing did not result in increased transmission. Even more interesting, only 2% of close contacts monitored during the study period became positive, questioning the need for any quarantining policy.

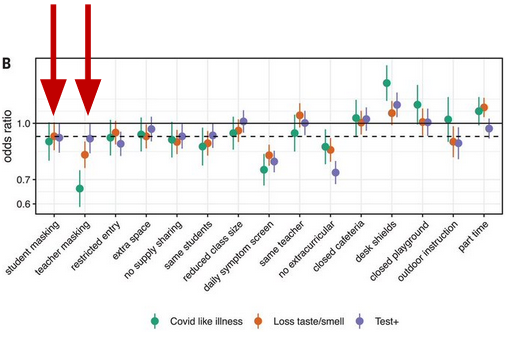

Furthermore, as rates of vaccination have increased in adults, it has become even more clear just how resistant most children are to severe disease and death from COVID. In a U.K. study of vaccine efficacy, unvaccinated children were less likely to die from COVID that vaccinated adults at any age:

When considering the global preponderance of evidence, it becomes difficult to imagine a positive effect from the reported zero to modest benefits of school masking and quarantining of close contacts on school transmission. The real benefits of these measures are unclear despite an onslaught of biased media coverage and politically-motivated messaging by government agencies. Yet the costs of disrupting education are clear. Education and child mental health are more important than a political victory lap for achieving high vaccination rates, especially a victory lap that’s based on exaggerated harms and only the appearance of safety.

Reprinted from the author’s substack.

The post Hurting Children to Protect Them appeared first on Brownstone Institute.