Why Is the Human Being Not Like a Machine?

In defense of regulatory mandates during oral arguments, the following words were spoken by Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor: “Why is a human being not like a machine if it’s spewing a virus?” For her, it is a simple matter: regulatory impositions rule the machine world so why not the human one too?

The question came across to listeners (millions heard these arguments for the first time) as shocking. How can anyone think this way? Human beings carry pathogens, tens of trillions of them. Yes, we infect each other, and our immune systems adapt as they have evolved to do. Still, we have rights. We have freedom. These have granted us longer and better lives.

The Bill of Rights doesn’t pertain to machines. Machines don’t comply with Constitutions. Machines have no volition. Machines are things that must be powered by external sources, programmed by humans, and behave exactly as they are managed to behave. If a machine doesn’t do what is expected, it is broken and therefore repaired or replaced.

All this seems incredibly obvious and undeniable, so much so that one can only stand back in awe that anyone would doubt it, particularly a judge who holds the fate of human liberty in her hands. It seems utterly astonishing that such a person would not quite grasp the difference between the human experience and a mechanized widget.

And yet, what she said is actually not out of left field. It wasn’t a point she made up on the spot. The presumption that people should be managed like machines has been a baseline assumption pervasive in pandemic planning for the better part of 15 years. The delusion was born in the heads of a handful of people who happened to be close to power, and it has grown ever since.

Many great thinkers have tried to blow the whistle on these intellectual trends for a very long time. Twenty years ago, Sunetra Gupta warned us. Nonetheless, the modelers and planners carried on, building more models, fantasizing of central plans, cobbling together mitigation strategies, and otherwise plotting to remove human volition from the list of unknowns during a pandemic.

In other words, treating people like machines is not a radical idea and it is not purely the cranky invention of an ideologically motivated court judge. What Sotomayor said isn’t unusual at all, at least not in the confines of her intellectual bubble. She offered up a summary statement concerning many of the presumptions behind lockdowns and now mandates. It has been part of the agenda for a very long time, a view held by some of the world’s leading intellectuals that gradually gained influence within the epidemiological profession over the last decade and a half.

All of this is well documented. We just hadn’t fully experienced it until 2020. That was the year in which they found the opportunity to test the theory that humans can be managed as machines and thereby generate better results.

Have a look at Michael Lewis’s mostly awful book on the topic. For all its failings, it does a deep dive into the history of pandemic planning. It was born in October 2005 at the urging of president George W. Bush. The innovator was a man named Rajeev Venkayya, who today runs a vaccine company. Back then, he was head of a bioterrorism study group within the White House. Bush wanted a big plan, something similar to the big vision that led to the Iraq War. He wanted some means to crush a virus. More shock and awe.

“We were going to invent pandemic planning,” Venkayya announced to the staff. He recruited a group of computer programmers who had zero knowledge of viruses, pandemics, immunity, and no experience at all in the management and mitigation of diseases. They were computer programmers and their programs all presumed exactly what Sotomayor said: we are all machines to be managed.

Among them was Robert Glass from the Sandia National Laboratory, who cobbled together the idea of social distancing with the help of his middle-school-aged daughter. The idea was that if we all just stayed away from each other, the virus would not transmit. What happens to the virus? It was never clear but they believed that somehow a virus that could not find a host would then somehow disappear into the firmament, never to return.

None of it ever made sense, except in the models. In the world of computer modeling, everything makes sense according to the rules as set up by programmers.

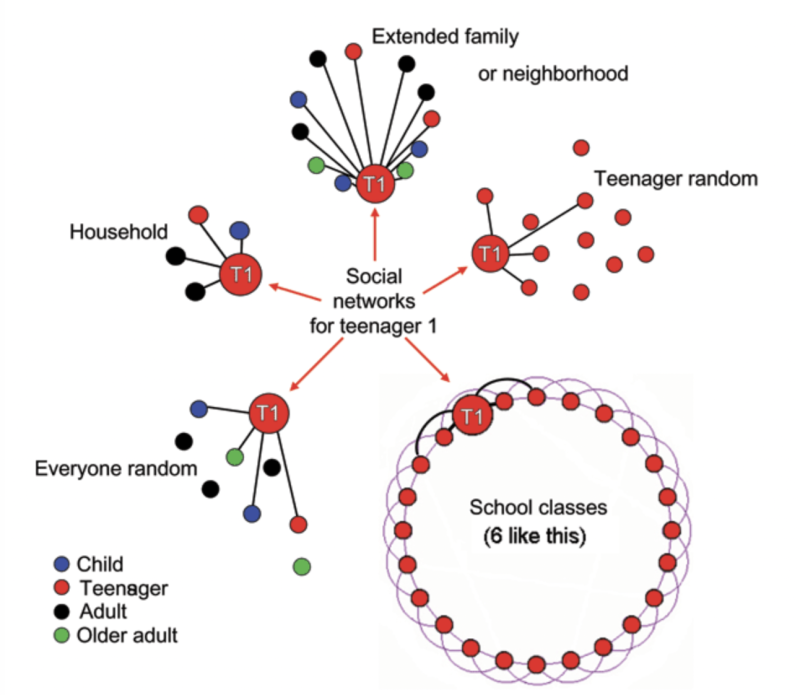

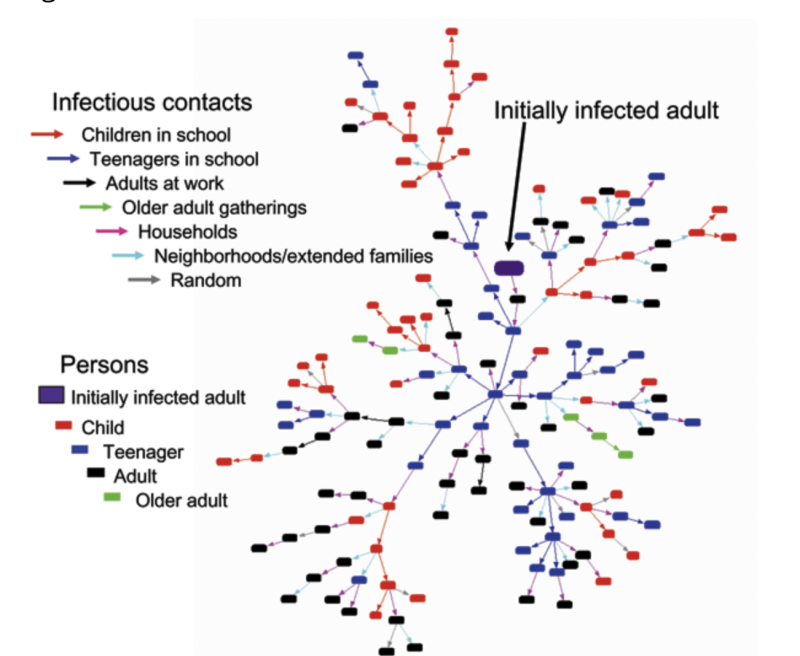

You can read the original Glass paper on the CDC website, where it still lives today. It is called Targeted Social Distancing Designs for Pandemic Influenza. It’s a central plan that removes all human volition. Everyone is mapped according to their likelihood of spreading disease. Their choices are replaced by the plans of scientists. The model is based on a small community but it applies equally to an entire society.

Targeted social distancing to mitigate pandemic influenza can be designed through simulation of influenza’s spread within local community social contact networks. We demonstrate this design for a stylized community representative of a small town in the United States. The critical importance of children and teenagers in transmission of influenza is first identified and targeted. For influenza as infectious as 1957–58 Asian flu (≈50% infected), closing schools and keeping children and teenagers at home reduced the attack rate by >90%. For more infectious strains, or transmission that is less focused on the young, adults and the work environment must also be targeted. Tailored to specific communities across the world, such design would yield local defenses against a highly virulent strain in the absence of vaccine and antiviral drugs.

Here is a small map of infection transmissions as presented in this seminal paper.

Wait, this is my community? This is society?

You see here how this works. They have mapped what they imagine to be the infection path. They replace this path with closures, separations, capacity limits, travel restrictions, forcing everyone to stay home and stay safe. You wonder why they targeted schools? The models told them to.

Thus pandemic planning was invented, contradicting a century of public health experience and a millennia of knowledge concerning how pandemics really end: through herd immunity. None of this mattered. It was all about the models and what seemed to work on their computer programs.

As for human beings, yes, in these models, they are machines. Nothing more. When you hear the claims reduced to preposterous quips by a judge, they are laughable on their face. Or scary. Regardless, they are plain wrong. Surely every intelligent person knows the difference between a person and a machine. How can a person believe this?

But in a different context, you can take that same worldview, throw up some colorful charts, back it by a Powerpoint presentation, add variables that can change the model’s workings based on certain presumptions, and you can generate what appears to be a highly intelligent computerization that reveals things we otherwise would not see.

Blinded by science, we might say. Many people in the White House were indeed blinded. And the CDC too. They had hoped to deploy the newly codified system of virus control in 2006, with the Avian bird flu, which, experts warned, could kill half of the people who got the bug. Anthony Fauci said the same thing: a 50% case fatality rate, he predicted.

And yet many people were disappointed: the bug never jumped from birds to humans. They could not try out their great new scheme. Still, the modeling movement grew steadily over a decade and a half, gaining recruits from many sectors, and then enjoying enormous funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Obviously Gates himself was and remains convinced that the best way to deal with pathogens is through antivirus programs we call vaccines, while otherwise mitigating spread through human separation.

In 2006, I had speculated that disease planning was a new frontier for state control of the social order. “Even if the flu does come,” I wrote, “the government will surely have a ball imposing travel restrictions, shutting down schools and businesses, quarantining cities, and banning public gatherings. It’s a bureaucrat’s dream! Whether it will make us well again is another matter.”

“It is a serious matter,” I continued, “when the government purports to plan to abolish all liberty and nationalize all economic life and put every business under the control of the military, especially in the name of a bug that seems largely restricted to the bird population. Perhaps we should pay more attention.”

At the time, most people just ignored all this as so much noise. It was just another White House press conference, just another wacky bureaucratic dream from which our laws and traditions would protect us. I wrote about it not because I believed they would attempt it. My alarm was that anyone could dream up such a crazy plot to begin with.

Fifteen years later, that noise became the calamity that has fundamentally destabilized American liberty and law, wrecked trade and health, shattered countless lives, and thrown our future as a civilized people into grave doubt.

Let us not turn away from the reality: all of this was a product of intellectuals who did and do think exactly as Sotomayor. We are not humans with rights. We are machines to be managed. In fact, if you look back at the March 16, 2020, news conference at which these lockdowns were all announced, Dr. Birx said just in passing the following sentence:

“We really want people to be separated at this time, to be able to address this virus as comprehensively that we cannot see, for we don’t have a vaccine or a therapeutic.”

Here we have a leading advisor to the president essentially advocating for completely new and radical social transformation, as managed by public health professionals. A comprehensive plan for everyone to be separated, exactly as the disease planners 15 years earlier had advocated in their hare-brained computer models.

Why did reporters not ask more questions? Why did people not scream that this whole cockamamie scheme is inhumane and deeply dangerous? How could people have sat calmly listening to this gibberish and pretend it was normal?

It’s sheer madness. But madness can transverse the decades so long as its creators live within intellectual bubbles, enjoy generous funding, and never have to confront the results of their schemes.

This is the story of what happened to liberty in the US and all over the world. It was shattered by fanaticism, all rooted in a core presumption that we’d be far better off as human beings if our ruling class regarded us as no different from machines spewing sparks. They were permitted to reorganize the whole of our lives based on that principle.

What the Justice Sotomayer said strikes us now as both dangerous and delusional. It is. And yet her conviction is widely shared, and has been for at least 15 years, among the class of intellectuals who gave us lockdowns and pandemic controls. It’s their template. At their parties and conferences for all these years, such thoughts were considered normal, responsible, intelligent, and wise.

Now that they have had a go at it, where are they to defend the results? Instead, they have mostly left the scene, leaving the bag of intellectual rubbish in the hands of a Supreme Court justice who is both their accidental mouthpiece and their sacrificial victim. It was the statement that will define her career, forever cited as proof that she should never have been approved for that position.

In fact, what Sotomayer said about machines and humans was not rooted in ignorance as such; it was the fulfillment of the delusions of countless intellectuals the world over for most of this century. She was summarizing countless papers and presentations in the form of a casual quip, thus revealing it for the fundamental insanity that it truly is.

“Madmen in authority,” wrote John Maynard Keynes, “who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.” Sometimes that very distillation is what reveals precisely what we’ve tried so hard for so long to ignore. Sotomayer revealed the existential threat, in a way that was mortifyingly ridiculous, but also encapsulated everything that has gone wrong in our times.